From Redruth to 41°43′57′′N 49°56′49′′ W by Tim Koch

- Amanda Harris

- Aug 15, 2025

- 8 min read

August 2025

Tim tells a story of a journey that started from Redruth in hope but that ended thousands of miles away in tragedy.

In early April 1912, Frank Andrew, a 26-year-old tin miner, left his home in Four Lanes and made his way to Redruth Railway Station, three miles away. Whether he was accompanied by his pregnant wife of four years, Rhoda, and his daughter Lucy who had been born four months into the marriage, we do not know. Either way, it would have been a tearful departure as Frank was on his way to find work over three-and-a-half thousand miles away in the copper mines of Houghton in the American state of Michigan. The intention was for his family to join him when he was established.

Houghton, once a significant hub for Cornish miners (and one that still proudly preserves its Cornish heritage), is part of Copper Country, an area of Michigan so named because in the late 19th and early 20th centuries it was the world's greatest producer of copper. Cornish miners, skilled in extracting metals embedded in hard rock, were much in demand there.

By the time of Frank’s departure, the great waves of economic migration from Cornwall had passed and what movement abroad that did exist was, in relative terms, piecemeal. In my previous piece for Departing from Redruth Station titled Redruth to The Rand, I noted that the Cornish Diaspora was:

… the 18th and 19th century emigration of many thousands of Cornish people, many of them skilled miners driven abroad by the decline of local mining. In each decade from 1861 to 1901, around twenty-percent of the Cornish male population migrated abroad – three times the average for England and Wales and 250,000 in total.

I also quoted a reference to the last mass Cornish migration in John Nauright’s study of Cornish miners in South Africa: Every Friday morning from 1890 to 1900 the up-train from West Cornwall included special cars labelled “Southampton”, the embarkation port for South Africa.

By the time of Frank’s departure, there was no direct Southampton train from Cornwall and what migrants there were would depart from Redruth and other stations along the line in quiet isolation.

Once in London, Frank would have to make his way across the capital from the Great Western Railway’s Paddington Station to the London and South Western Railway’s Waterloo Station and catch the so-called American Boat Train to Southampton, the dock that had recently replaced Liverpool as the departure point for transatlantic liners. Perhaps this was a daunting task for a Cornish lad who may not have left the county before.

For all Frank’s possible fears about making his transport connections and his undoubted sadness at leaving his home and family, as he crossed the Tamar and left Cornwall further and further behind, his thoughts may have started to focus on the positive aspects of his upcoming adventure.

Frank may have known, or would soon be happy to discover, that there were other Cornish miners travelling with him in the second class accommodation on his ship to America. Notably, there were four who were also going to the mines of Houghton. They were Fredrick Banfield (28), who was born in Helston but was latterly living in Plymouth, while William Carbines (19), Joseph Nichols (19) and Stephen Jenkin (32) all came from the St Ives area.

While he would not be aware of the exact number, Frank would know that there would be plenty of other Cornish men and women on his ship, all in search of a better life. In fact there were 62 Cornish born in all: 36 in 2nd Class, 15 in 3rd Class and 11 amongst the ship’s crew.

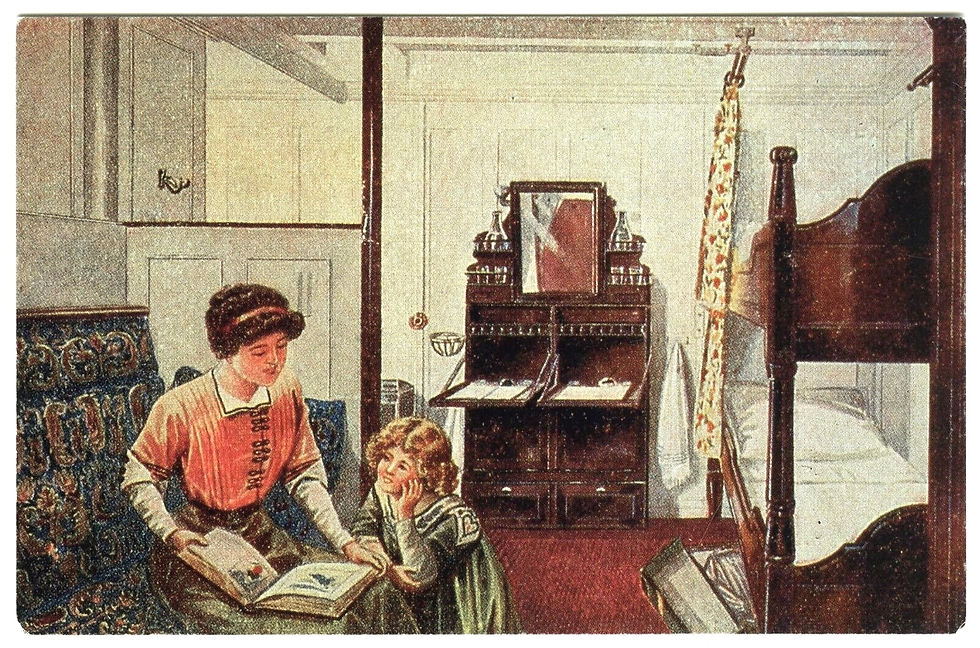

The Cornish have a reputation for thrift so it seems a paradox that most elected to pay the £6 extra (equivalent to £875 today) to travel in 2nd, not 3rd class. We can speculate on why but we do know that Frank and his fellow 2nd class passengers would have been spared the indignity put upon those in 3rd Class of having medical checks for lice and trachoma on boarding.

Many of the 62 may have been comforted by the fact that there were hotels by and for Cornish people both at their departure point in Southampton (such as The Cornish Hotel near the Eastern Docks) and at their disembarkation point in New York (such as the The Star Hotel on the Lower West Side).

Finally, Frank would surely be excited by the fact that the ship that he was travelling on was newly built and was the most advanced and luxurious passenger vessel then in existence. At the time it was the largest movable object in the world, a sixth of a mile long, the height of a five storey building and with a rudder the size of a cricket pitch.

The owners, the White Star Line, had named the great ship, Titanic.

Historian, Richard Davenport-Hines:

The Titanic was a floating microcosm of Edwardian society - at the bottom of the ship was third class, filled with economic migrants and political and religious refugees hoping for a better life in the New World. Above them were hundreds of second-class passengers buoyed up by their prosperous respectability. On the upper decks were the hereditary rich and those of inconceivable wealth…

Four days into its maiden voyage at about 600 kilometres south-southeast of Newfoundland (strictly, 41°43′57′′ N 49°56′49′′ W) Titanic struck an iceberg at 11.40pm on 14 April. Two hours and forty minutes later at 2.20am on 15 April, the ship sank beneath the sea and within twenty minutes, the 1,514 people not in the lifeboats would have died of hyperthermia or drowning, leaving just 710 alive. The victims included Frank Andrew and the other four Cornish miners heading for Michigan: William Carbines, Fredrick Banfield, Stephen Jenkin and Joseph Nichols.

William’s body was eventually recovered and identified. It was sent home and was buried in St Ives. He would have been returned to Cornwall in a canvas bag, only 1st Class cadavers merited wooden coffins.

Fredrick, Stephen and Frank’s bodies were not recovered or, if they were, not identified. There is a memorial to Fredrick on the family gravestone in Helston and to Stephen on the family memorial in St Ives.

Frank probably has no memorial. His widow, 25-year-old Rhoda was pregnant when he left and she gave birth in October 1912. She remarried in November 1913 and had seven more children, dying in Four Lanes in 1967. Daughter Lucy lived to the age of 93 and died in Penzance in 2001.

Joseph had been travelling with his mother, Agnes Davies, and his eight-year-old step-brother, John. Twenty-five minutes after the iceberg struck, they ignored their steward’s advice and went on deck. Agnes and John were placed in a lifeboat but when the nineteen-year-old Joseph asked permission to join them he was told by an armed ship’s officer that he would be shot if he tried - even though there were spaces in the boat. Joseph’s body was recovered eight days later but it was too damaged to be embalmed and so he was buried at sea where he was found.

Statistics can be tedious and uninformative but some concerning Titanic are illuminating.

Of all the 62 Cornish born people on board, only 15 or 24% survived. This does not compare well to the overall survival rate of 32% for all 2,224 but is probably accounted for by the absence of any Cornish born in 1st class (which had a 61% survival rate) and by the disproportionate number of Cornishmen (49) compared to Cornishwomen (13) on board as, contrary to popular belief, survival depended more on gender than on class.

Overall, 75% of women survived but only 20% of men. Perhaps the most surprising fact about the Titanic is that more women from 3rd class were saved than were men from 1st class (76 to 57). First class women fared best, only four out of 144 died.

Of the 36 Cornish born people in 2nd class, seven of the eight women and all five children were saved but all 23 of the men died. The Cornishwoman that died, Sarah Chapman from Liskeard, could have got into a lifeboat but she refused to be separated from her husband. Overall, the survival rate for men in 2nd class was 8%, for women 86% and for children 100%.

Of the fifteen Cornish born people in 3rd class, none of the eleven men and four women survived compared with an overall steerage survival rate of 16% for men and 46% for women.

Eight of the eleven Cornish crew members died.

The experiences of the Cornish on the Titanic highlight broader themes: the hope and desperation that drove people to leave their homelands, the risks of long-distance migration, and the arbitrary nature of survival in disaster. Though small in number, the Cornish aboard the Titanic were symbolic of the wider diaspora and struggle for a better life that characterised the era.

Part 2 will look at some common misconceptions regarding the sinking of the Titanic and will try to put human faces to some of the Cornish statistics.

I am grateful to the remarkable website Encyclopaedia Titanica from which I gathered much of the information used in both Part 1 and Part 2. TK.

Thank you Tim for this fascinating and very moving account. I shall be seeking out Frederick Banfield's memorial in St Michael's graveyard in Helston. The second part of Tim's blog will be published on August 29th. You can read more of Tim's writing http://heartheboatsing.com/ where he is a regular contributor

Comments